Riding Where Land Loosens

I took off my helmet, looked at Dalma, and asked “what did we just do?”

We’d just gone for a ride. That was it. No destination. No objective. No sense that we were going anywhere in particular. Just riding for the sake of riding, looking around, turning when the road suggested it. Which, for Dalma particularly, felt oddly unfamiliar. She’s often struggled to ride…well…nowhere. She’s always needed a destination. Riding, in her head, has usually been a means to an end — transport disguised as pleasure. You go to something. The ride is how you get there. This felt different. Aimless, even. Slightly unsettling. On foot, getting lost feels playful — what’s around the next corner? On a bike, it’s a different kind of lost. Less curious, more existential. Not where might this lead, but where exactly am I, and why?

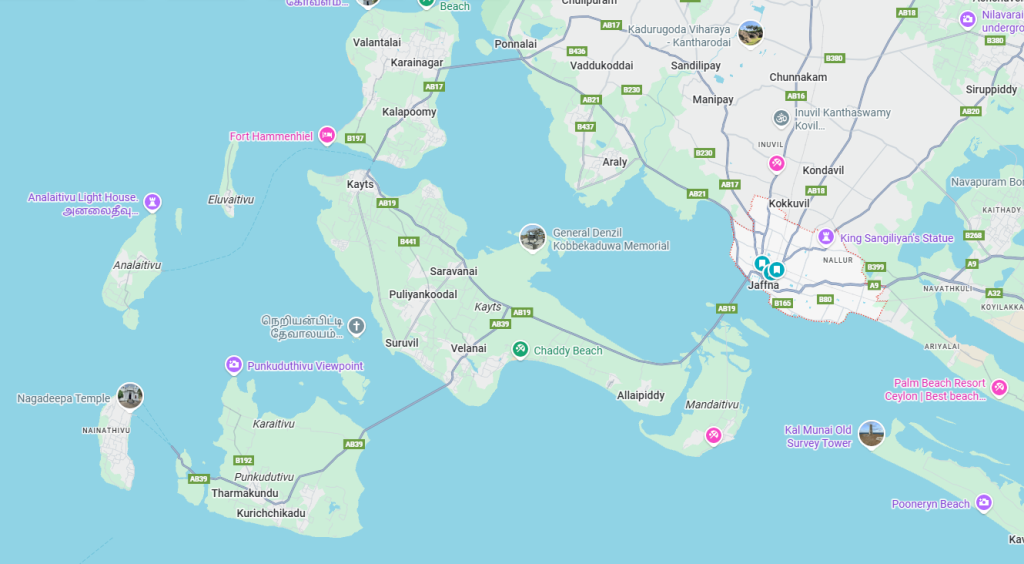

We rode out this morning under an overcast sky. Jaffna breaks up into a series of islands—what my friend Phil, scholar that he is, would call an Esturine Landscape. Lots of islands connected by bridges and ferries. The land around Jaffna was salt water flats and this seemed a fascinating part to explore. Maybe a kilometre of traffic and basically from the centre of Jaffna, there was a long viaduct road, a bridge build on a pile of rocks. We rode it with drizzle splattering and trying to watch the road where there were fishermans huts on stilts, multicoloured and peeling boats, and such things that might distract you into the path of another vehicle. If you’ve ridden overseas, you’ll know this battle of attention.

We rode across it, and onwards. The islands seemed less populated than the mainland. At one point, on a whim, I turned left and rode down a small road and kept going until we got to the coast. We rode along a small road. I reached down to turn off the navigator. I’m pretty good at missing turns and getting lost, but this was one time I didn’t want to know where I was.

We were on Kayts, the northern and largest island, just sound of Jaffna. We rode around for a while looking and just…being…you know? Eventually we headed south for the islands of Pungudutivu. The road there stood out. Barely wider than a single lane. No railings. No shoulder. Just road, air, and water. It’s remarkable how much psychological comfort a thin strip of metal provides. It doesn’t actually stop much — but without it, you suddenly feel very aware of gravity and your own fallibility. Two trucks almost came to grief trying to pass each other. The wind was strong, sometimes pushing the bike sideways hard enough that it felt like riding at a permanent lean. Beautiful, but demanding.

If Kayts had seemed remote, Pungudutivu seemed like it was on the moon. What struck me most, though, was how people lived out there — communities built right on the water. Fishing huts, small houses, life arranged around tides rather than streets. At one stop, we looked out over shallow waterways weaving between homes, connected by little strips of land. If it hadn’t been salt water, I’d have assumed it was flooded farmland or rice fields. Instead, it felt almost parcelled — water divided into purposeful shapes. Functional, but strangely elegant.

We’d planned to ride to the very tip of the island — the end of the road, the end of the idea — but the surface broke up into something our small road bikes, unknown tyres and all, really didn’t need. We turned back a few kilometres short. Not quite the end of the world, but close enough to feel the intention.

We rode back toward Kayts, intending to continue on to the third island, Kovilam. Along the road were houses in various stages of collapse — places that had once been substantial, even grand, now softened and dismantled by time. Roofs sagged. Walls were split open. Plants had moved in decisively, filling rooms where people clearly once lived. Later, we learned that many of these houses were likely abandoned during the civil war, when the islands were held by the LTTE and formed part of a strategic stronghold. But even without that knowledge, the houses carried a weight of absence. They didn’t look temporarily deserted. They looked finished with. They stood quietly back from the road, neither restored nor demolished, not memorialised, not explained. Just there. Unused. Unclaimed. The sort of ruins that don’t ask for attention, but keep it anyway — reminders that this island, like so many others, has a history that still hasn’t entirely let go.

Riding on, what stayed with me was the quiet. Apart from the wind, there was almost nothing. People waved as we passed. Riders nodded. It felt more remote than anywhere we’d been so far — maybe even more than Mannar. Remote not just geographically, but emotionally. A place where things aren’t in a hurry to explain themselves.

We weren’t able to get to Kovilam. The ferry was closed because a large rain event was expected, so we turned our bikes for home. Tomorrow, the forecast says rain. Heavy rain. Possibly days of it. Which means we’llmay stay put longer than planned. Again. First illness, now weather. This trip has a habit of inserting pauses where we didn’t schedule them.

That’s okay. We have time. We’re not chasing anything.

The ride was beautiful — dramatic even under cloud — and honestly, the weather was perfect for riding. Cool. Calm enough. It would be a shame to miss some of the places ahead if rain closes roads or makes climbs impossible. Sigiriya, for example, may or may not be an option.

But we’ll see. Things are supposed to settle after the 11th. We’re not due anywhere until the 26th. Time, for once, is not the constraint.

That seems to be the theme.

And yes — that’s who we are.